Khaki (UK /ˈkɑːkiː/ and US /ˈkækiː/) is a loanword incorporated directly from Hindustani (Urdu or Hindi) ख़ाक /ﺧﺎﮐﯽ meaning "dust-colored." It is originally derived from the Persian, ﺧﺎک Khâk, literally meaning "soil." (Merriam Webster Dictionary)

The word was adopted into the English language via the British Indian Army. In the military, the iconic royal red uniforms would grow ‘khaki’ as they became covered in dust. New uniforms were then created in murky greenish-yellow color in order to conceal the ubiquitous dirt and dust of the region, but also to camouflage the soldiers amidst an arid landscape. Civilian culture has since appropriated the military origins of the colour and styling it into ‘khakis,’ which have become an iconic garment for the well-behaved person.

The Khaki color alone, without historical or etymological context, has rich complexities. Like the color grey, khaki exists within a spectrum (various shades of olive green to milky beige). The sliding scale definition has made grey-ness synonymous with ambiguity. It requires a discerning eye to interpret the nuances between each shade. However, grey colors are plotted linearly, mixing only black and white, while khaki hues are mixed from almost every color forming a radial spectrum of mixtures. To interpret this colour one must expand the edges of the grey-zone, beyond binary extremes.

Though khaki is everywhere, it goes less noticed and less celebrated for the very reason that it achieves its goal of neutrality, camouflage, and middle-ness. But just because we don’t see it, certainly doesn’t mean it’s not there. Like its origin in military camouflage, khaki hides in plain sight. Khaki is the neutralising background hue of our polarising modern society. Armed with its properties and history, we use it metaphorically to interpret our information systems, politics and technology.

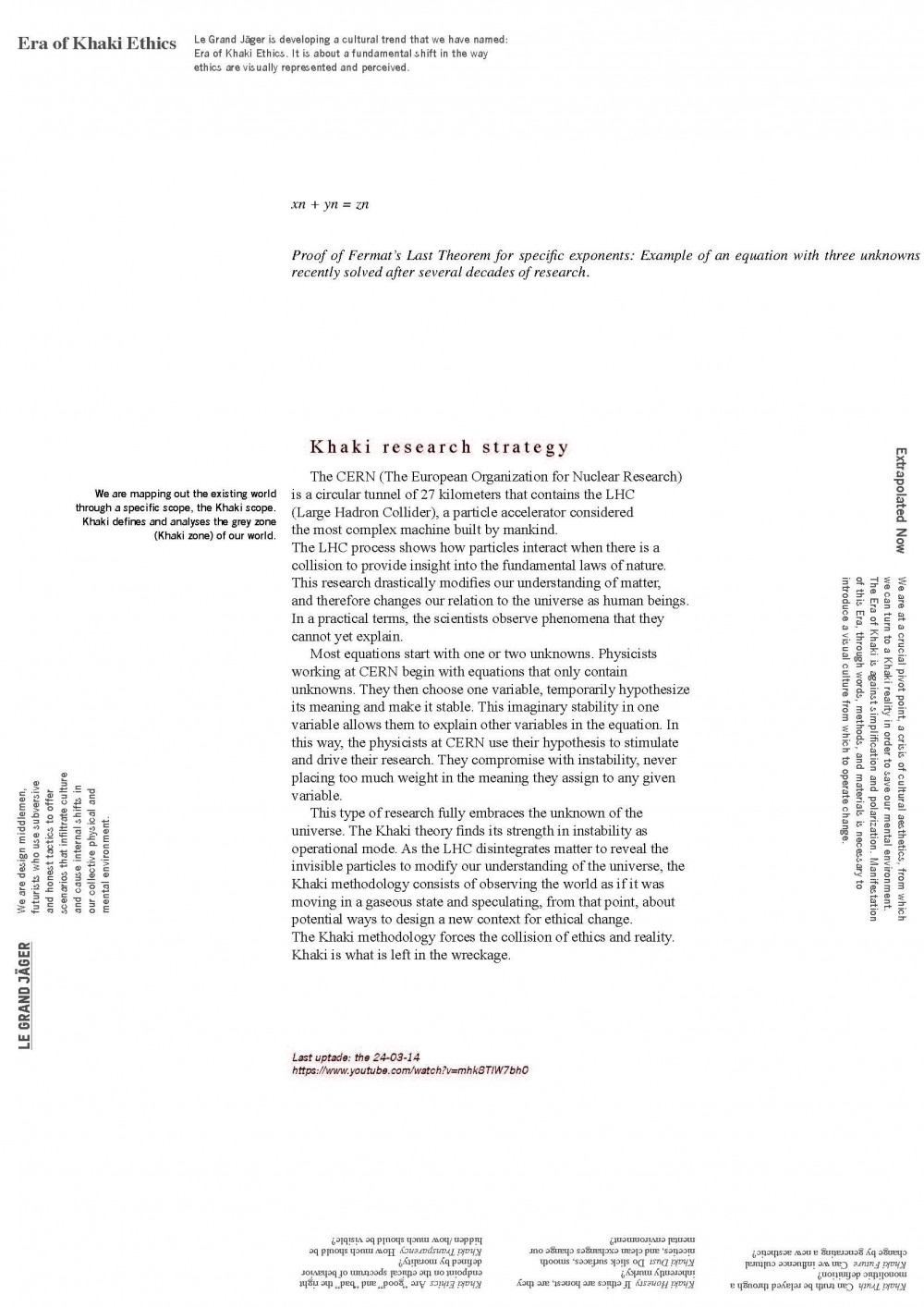

Khaki properties, khakiness, can be recognised in our networked information systems. As opposed to previous regimes that would deprive their citizens of information in order to gain control, today we are bombarded with layer upon layer of information, narratives and conflicting facts (a multiplied transparency that ultimately makes everything opaque). Each of these is backed up by varying versions of truth, in which real truth is inextricably camouflaged amongst so many ‘dust colored’ layers of information. The real facts hide among the “alternative” ones, requiring an understanding of nuance and complexity to sift through the spin and sensationalism of the modern media cycle.

From this polarising rhetoric, we see an increase in hyper-polarized or extremist political groups, like ISIS or the Alt. Right. We see these forces as opposed, but the extremism of one is simultaneously caused by and fueling the extremism of the other, creating a feedback loop of concrete views. The only way to escape this loop is to see the enemy in khaki terms. ISIS, it can be argued, is the ultimate enemy in a khaki era. With no one nationality, age or frontline ISIS soldiers are a mosaic of identities and motivations. Their call to arms is an ideology and thus iterative depending on where that ideology surfaces. The far right and jihadist groups both benefit when we polarise and ‘other’ opposing points of view.

This prevailing denial of complexity exists not only in political rhetoric and actions, but has become a part of our new visual scope. New technology has fundamentally shifted our ways of seeing, prioritizing width over depth. This bird’s-eye-view is not only a common angle at which to see imagery today (made popular and accessible by drones and tools like google earth, CCTV, selfie sticks) but also represents the way we capture ideologies. The weaponized drone allows us to see wide swaths of visual information, however in perilously shallow depth. In time, our militaries will have no choice but to formulate new ethics around how to interpret and make calls based on the limitations of this vision. But for the moment, these technologies are indicative of how we have come to ignore the details.

And because we are uncomfortable in khakiness, we seek simple solutions to clear the air. Politicians, thought leaders, and brands feed our natural desire to clear the fog by replacing the intricacy with simple narratives. As khakiness is edited out of headlines, imagery, and rhetoric, so goes our communal ability to read nuance. And this ever increasing gap between for instance, the slick ad campaign and the reality of that company's practices, is aiding our inability to see truth, and fundamentally changing the essence of our ethical, cultural, and aesthetic systems.

This erasure is subtle, manifesting insidiously throughout society as soft propaganda slowly chipping away at our ability to interpret nuance. Like sand in a gear, it doesn’t halt the machinery but rather grinds away at it’s moving parts until there is no more friction.

As designers and artists offering a visual language, we should hold ‘khaki content’

dear–embrace the very nature of khakiness, as it is the only part of our political and visual culture that cannot be weaponised. We can build a new literacy of complexity that amplifies our collective ability to interpret nuance.